Every second Sunday in August, the Octavia Hill Society pays homage to the memory of the subject of their organisation by taking a coach trip. Often the destination is Crockham in Kent, where Octavia Hill lived and indeed is buried. This year, however, the Society chose to devote their trip to Octavia Hill's colleague and fellow campaigner for open spaces (and co-founder of the National Trust), Sir Robert Hunter.

The timing was far from accidental. While last year marked the centenary of the death of Octavia Hill in August 1912, this year marks a hundred years since Sir Robert Hunter died in November 1913. Hunter is a less well-known figure than Hill, perhaps in part because of the order in which they died. Had Hunter been the first to pass, one wonders if his role as the first Chairman of the National Trust, and indeed as the person who devised the legal concept of a trust to whole land and buildings for the benefit of the nation, might be better remembered.

Our coach trip traced a journey from south London out to Haslemere in Surrey, where Hunter spent the last thirty years of his life and where he is buried. As it turns out, though, our journey was more or less entirely confined to the historical boundaries of Surrey. Before London had its modern-day boroughs, the county of Surrey stretched all the way to the Thames. It encompassed all that land south of the river, which is today in the boroughs of Lambeth, Wandsworth and Southwark. It's the reason why The Oval Cricket Ground is still today the home of Surrey Cricket Club.

Our road trip on the hunt for Hunter began in Addington Square, Camberwell, where we were welcomed by a local historian and a party from the residents association, all keen to share their own knowledge of the Hunter family's time in the Square. Hunter was born here, in a relatively modest house in the corner of the Square. The family moved to a larger home a few doors down after Hunter's father returned from sea (he was a successful mariner).

From Camberwell we struck out to Wimbledon, via the south London commons of Clapham and Wandsworth. Clapham Common remains a popular open space, although its future seems never to have been under threat. The Common has always had its wealthy supporters, living in the large mansions that abut it on each of its sides. Wandsworth Common, however, faced significant threats in the mid 19th century from those who would rather see it developed into housing and transport routes. The common is now bisected by train lines running in and out of Clapham Junction.

This was the context in which Hunter himself first came to prominence. As a young lawyer he entered a prize competition for essays on the best protection for metropolitan commons. His essay was highly commended, and brought him to the attention the Commons Preservation Society, founded in 1865 to fight against the enclosure of London's commons. Hunter's intelligence and legal expertise led to him being appointed Solicitor to the CPS. There followed some 15 years of legal battles over some of the most famous open spaces around London: Wimbledon Common, Hampstead Heath and Epping Forest.

We stopped at Wimbledon to admire the windmill in the middle of the common, and also to view items from the collection of the Wimbledon Society (including an edition of the essay that Hunter wrote in 1866). Already here a link to Octavia Hill emerged. Octavia's mother met her father, James Hill, while she was teaching in Wimbledon. The museum's collection includes reference to Hill being asked to campaign for the preservation of the remains of Wimbledon Park (in fact a private estate, where the lawn tennis club is now located).

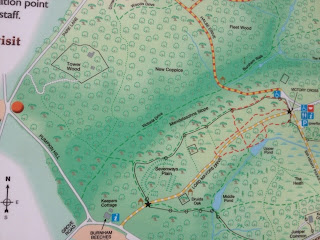

Keeping once again to the A3 (which formed the backbone of our route for much of the day), we headed out of London to Hindhead in Surrey. Our journey took us through the Hindhead Tunnel, opened in 2011. A happy consequence of the tunnel's opening has been that the commons above it have been reunited. Trees are being felled in order to return the landscape to the open heath that it formerly resembled.

Our final stop was at St Bartholomew's church in Haslemere. Hunter moved to the town in 1883 with his young family not long after he had been appointed as Solicitor to the General Post Office, a role he held until just before his death in 1913. At the church we planted an Octavia Rose in the churchyard, a fitting tribute to Octavia's great colleague and fellow campaigner for open spaces Sir Robert Hunter.