I visited Burnham Beeches in Buckinghamshire for the first time last weekend, and was delighted to find both a beautiful area of woodland and a connection with the early commons preservation movement.

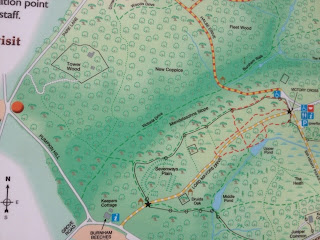

Burnham Beeches comprises 220 hectares of woods in South Buckinghamshire, 25 miles or so from London. Its many miles of walks take visitors through areas of ancient woodlands, wood pasture, open spaces and heaths. The woods get their name from the many veteran beech pollards that provide such an amazing backdrop to an afternoon’s stroll, as well as habitats for wildlife (such as the red ants we saw in nests all over the place).

Curiously, perhaps, the place is owned and managed by the Corporation of the City of London. Why should the City of London concern itself with some woods so far from the City? One of the drives – Sir Henry Peek’s Drive – gives a clue as to what happened.

In 1879 the woods were put up for purchase, as ‘land suitable for the erection of superior residences’. The Commons Preservation Society and the Kyrle Society, which at the time were vocal defenders of open spaces, decided something needed to be done.

Since part of the wood was common land, the Corporation was invited to make use of the Open Spaces Act of 1878, which gave them the power to purchase such lands for the benefit of the public within a radius of 25 miles of London. The Corporation had no powers to purchase the remaining, enclosed areas, and were saved when the local MP Sir Henry Peek stepped in. He offered to buy the residual, non-commonable areas of Burnham Beeches, in order to donate them to the Corporation and re-unite the whole.

Sir Henry Peek was a well-known figure in the open spaces movement, and had been a big influence in the battle for Wimbledon Common in 1864, which had been the starting point for the Commons Preservation movement. One of the contributors to an essay competition sponsored by Sir Henry, on the theme of the protection of commons in metropolitan areas, was a young London lawyer called Robert Hunter. His essay was awarded a highly commended prize, and Hunter went on to be one of the country’s leading experts on the law of common land as well as one of the founders of the National Trust.

|

| Sir Henry Peek, MP |

Hunter was closely involved in the struggle to save Epping Forest from enclosure, another woodland saved by the Corporation at around the same time as it acquired Burnham Beeches. Meanwhile, Octavia Hill, Treasurer of the Kyrle Society, viewed the Corporation’s acquisition of Burnham Beeches as a great success for the early open spaces movement.

No mention is made of the Kyrle Society, or the Commons Preservation Society, in the visitor centre at Burnham Beeches. Nonetheless, the woods clearly have an important place in the story of the commons preservation movement, and indeed a strong connection to the founders of the National Trust.

Incidentally, the connection with Sir Henry Peek, son of one of the founders of Peek Freans, also provides the missing link between the commons preservation movement and the garibaldi biscuit....

Incidentally, the connection with Sir Henry Peek, son of one of the founders of Peek Freans, also provides the missing link between the commons preservation movement and the garibaldi biscuit....

The other remarkable tree I made a fond return visit to last weekend was the Ankerwycke Yew. A very special tree indeed, and one with an even older significance, as potentially the site where Magna Carta was sealed. Read more at the Ankerwycke NT blogsite here.