Octavia Hill,co-founder of the National Trust, took up her association with Crockham Hill in Kent in 1884, when she took on a cottage there called Larksfield. I visited Crockham Hill today, after taking in two local National Trust properties: Chartwell, and Emmetts Garden. Octavia may have known of both places, though they only came to the Trust in the 1960s.

Hill was fond of Crockham Hill, which she used as her country retreat. As the name suggests, this is a hilly part of the country, with wonderful views across the wooded Weald. Hill was a great lover of the uplands, which took on a spiritual significance in her eyes. Hills brought one closer to God, and enabled God's kingdom to be surveyed and marvelled at. Little wonder that the National Trust acquired so many hills in its early decades - including (in addition to those in the Lake District) several in the vicinity of Crockham: Ide Hill, Toys Hill, Mariner's Hill.

Hill died on 13 August 1912, at the age of 73. She is buried at Crockham Hill church. A simple gravestone marks the plot, though Octavia's name (along with that of her companion Harriot Yorke) follows that of Miranda Hill, her sister, who died in 1910.

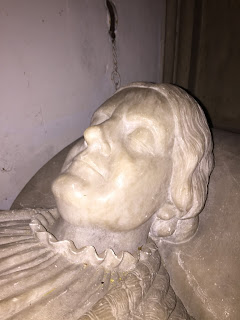

Inside the church is a full-length effigy of a recumbent Octavia Hill, to the left of the altar. It is a striking monument.

In one of the windows is a specially commissioned stained glass, installed in 1995 (the centenary of the founding of the National Trust), commemorating Hill's legacy.

It is a beautiful, peaceful church, in an idyllic part of the country: so close to the M25, yet it could almost be another world altogether.

Sunday, 2 August 2015

Sunday, 31 May 2015

Naming ceremony at Blakeney Point

I was thrilled to participate in a very special event

yesterday - the naming ceremony for the Francis Wall Oliver Research Centre on

Blakeney Point.

Blakeney Point is a dynamic spit of shingle and sand dunes

on the North Norfolk coast. The National Trust has been involved here for over

a hundred years. The Point was acquired for the Trust in 1912, using funding

from Charles Rothschild, and at the behest of Professor Francis Wall Oliver of

University College London.

Yesterday’s event was a naming ceremony for the building

that UCL continues to maintain on the end of Blakeney Point, adjacent to the

Trust’s distinctive Lifeboat House. UCL continue to use the building as a field studies research outpost, accommodating students keen to record nature on the BlakeneyPoint National Nature Reserve, just as Professor Oliver did a century ago.

The event was therefore a celebration involving three groups

of people in particular: research staff from UCL’s Centre for Biodiversity andEnvironment Research; National Trust staff; and members of the Oliver family,

including two of his grandsons, two of his great grandsons, and a great great

grandson.

It was a particular treat to see two pictures that were

brought along for the occasion: one, an interior painting of the UCL building

that was donated to UCL, the other a watercolour by Thomas Matthews Rooke of the National Trust

Executive Committee meeting on 15 April 1912 at which the acquisition of Blakeney

Point by the Trust was agreed. Shown as present at this meeting were Octavia

Hill (though, in fact, she was not there, as she was close to death by this

point), and Sir Robert Hunter, Chairman of the National Trust and a UCL

graduate himself (he studied logic and moral philosophy there from 1861 to

1865).

It was wonderful hearing recollections of boyhood stays on

Blakeney Point from Professor Oliver’s grandsons. It was also illuminating to

hear that Professor Oliver moved to Egypt later in his life, and lived near El

Alamein throughout the Second World War, continuing to live there even as the

famous battle raged around him. He later published one of the first scientific

papers on the impact of modern combat on the natural world, analysing the effect of tank treads on the desert landscape. This paper was

apparently long neglected, but was much consulted in the aftermath of the first

Gulf War.

According to his ODNB entry, Professor Oliver’s sense of humour was “reflected in his Who's

Who entry, where he listed his recreations as ‘once mountaineering, now washing

up’.”. There was much washing up to be done after yesterday's afternoon tea - thanks to the UCL team for organising such a wonderful event.

Friday, 15 May 2015

Wolf's Child at Felbrigg

Strange things are happening in the woods at Felbrigg at the moment. Each night, up to 250 visitors arrive for a performance that begins with a company of crows summoning up the bones of a wolf from a smouldering log fire, before leading the visitors on a walk through the dusky landscape.

The story of Wolf’s Child, which has been the star of this year’s Norfolk and Norwich Festival, involves a running battle between the ‘Mother’ and her regiment of chanting maids, who live their ordered lives within the safe confines of the mansion, and the pack of wolves that roam the unruly woodlands beyond.

The story explores what happens when one of Mother’s maids, Rowan, answers the call of the wild by joining the wolf pack. I mustn’t give too much more away, except to say that Rowan shows us one version of what we at the Trust might mean when we encourage people to ‘get outdoors and closer to nature’. The story explores the nature-culture divide, and demonstrates that however clever we two-legged human beings think we are, the crows are really the ones in charge.

If you get the chance to attend Wolf’s Child, please grab it and go while you can (it runs until 23 May). It’s such an inspirational glimpse of how places can be brought to life in new and interesting ways. The show has had rave reviews (including this one by Libby Purves).

It really is something very special, written and produced by WildWorks (who previously worked at Kensington Palace and on the Passion in Port Talbot).

Sunday, 29 March 2015

Runnymede, Magna Carta and the Anglesey Abbey connection

Magna Carta is perhaps the most famous example from history of a monarch

conceding powers to his subjects. The Great Charter of Liberties was agreed on

the meadows of Runnymede in Surrey 800 years ago this year in June 1215.

Runnymede is today managed by the National Trust, but it very nearly was

lost to development. Its open, natural character was only saved by the

generosity of the Broughton family, who also went on to bequeath Anglesey Abbey

near Cambridge to the nation. This link explains why visitors to Anglesey Abbey

are able to see numerous references to Magna Carta in the collections on

display in the house.

Magna Carta was a peace treaty between King John and his disgruntled

barons, who had been angered by years of excessive taxation and arbitrary royal

rule. The charter represented a colossal climb-down for the king, who not long

afterwards reneged on the agreement and plunged the country into civil war.

But Magna Carta survived. After John’s death in October 1216 it was

reissued in the name of his 9-year-old son and heir Henry III, in a smart piece

of statecraft by William Marshal, the king’s regent. The move was enough to end

the civil war and restore order.

Magna Carta went on to be reissued again several times by Henry III and

his successors, each an attempt to unify the nation by reaffirming the limits

of the king’s authority. King’s may have ruled by divine right, but Magna Carta

demonstrated that they operated within some commonly agreed constraints.

Two clauses in particular remain of fundamental importance to us today –

the freedom from arbitrary imprisonment, and the right to a fair trial. These

clauses are now regarded as the basis of our modern system of law and

governance, and are the reason why Magna Carta is still venerated, 800 years

on. The barons and King John himself could never have imagined it, but their

actions on that June day in 1215 changed the course of human history forever.

Magna Carta has not always been held in such esteem in the country of

its origin. By Shakespeare’s time, the charter had almost been forgotten (the

bard’s play about King John does not even mention it). Its significance grew in

the era of the Civil War, at a time when the limits of monarchical authority

were again under intense scrutiny.

But in many ways we owe it to our American cousins for keeping faith

with the Charter of Liberties. Its clauses directly influenced the USA’s

founding documents, and some US states still keep Magna Carta on their statute

books today.

This may explain why Urban Broughton, an English civil engineer who made

his fortune in America, chose to take a house near the meadows after returning

to England in 1912.

Urban had married the daughter of a wealthy American industrialist, and

the family’s fortune enabled them to acquire several properties in England.

Urban served as MP for Preston from 1915 to 1928, while his wife promoted

charitable causes in her adopted country.

In 1921 Runnymede appeared on a list of Government property that was up

for sale as development land. A huge local outcry ensued, and the coalition

Government of the time was forced into a u-turn, withdrawing the 252 acres of

meadowland from sale.

Ironically nothing at the meadows contained any link at all to the

events of 1215. For centuries the grassland had been preserved as an open space

not because of Magna Carta but because it was the venue for the Egham horse

races.

The pressure for development meant that the meadows’ future was far from

secure. Urban and his wife therefore offered to buy the meadows, in order to

save them for the nation. Urban was nominated for a peerage, but died in

January 1929 before he could assume the title.

Cara, his wife, became Lady Fairhaven, and his eldest son became the 1st Lord Fairhaven. Lady

Fairhaven and her sons purchased the meadows at Runnymede in December 1929 in

Urban’s memory, and passed them to the National Trust for protection in

perpetuity.

Lord Fairhaven by this time had also acquired Anglesey Abbey near

Cambridge. For more than thirty years he carried out extensive

improvements to the property, and filled it with fine art. A special gallery

was built simply to display Lord Fairhaven’s collection of views of Windsor

Castle, which include one of nearby Runnymede. His library meanwhile holds a

unique edition of Magna Carta, produced to mark its 600th anniversary in 1815

and printed using gold leaf.

A special LiberTeas event will take place at Anglesey Abbey on Sunday 14

June of this year, as part of the Magna Carta 800 celebrations.

This article appeared in the Cambridge News on Saturday 7 March 2015

The National Trust guidebook to Runnymede and Magna Carta - written by me! - is out now.

Bourne free

Bourne Mill in Colchester had a grand re-opening this week. On Wednesday, the mill was open for free to all-comers, to celebrate the fact that it has now moved to more regular, five-day a week opening hours.

Previously, the building was open only on occasional Sundays and Bank Holidays. Now, it boasts a single member of staff, a cafe and shop, and a team of 25 or so (and counting) volunteers.

The Trust acquired the building in 1936, a consequence of an anonymous donation. I don't know if this was anything to do with the mysterious Ferguson's Gang, who donated Shalford Mill in Surrey to the Trust in 1932. The story of Ferguson's Gang is endlessly fascinating - I've already placed my order for the new National Trust book that is coming out about them soon.

The Mill itself is a charming building, on the edge of a delightful pond. The building dates from 1591, though it is on the site of a former medieval mill.

In the 17th century it became a cloth mill, and then in the 19th century a corn mill. Its distinctive Dutch gables make it a very attractive building, in the midst of an area of 20th century housing.

The machinery inside has been carefully restored, and was operating when I visited.

It will be a lovely spot for summer days - let's hope they come soon.

Visitors coming by car may also find themselves passing near the curiously named Stalin Road - one of a number of nearby roads named after wartime leaders.

Sunday, 15 February 2015

On Northey Island

We had fabulous weather this weekend for a visit to the ever-fascinating Northey Island in Essex. Here are some photos.

The picture above shows clearly one of the sea walls that surround the farmland on the island. To the left is an area reverted to saltmarsh, with the scouring of mud caused by turbulence as incoming tides rebound off the sea wall itself. But at this point the sea wall is lower than the field to the right of it, and this wall was overtopped during the storm surge of December 2013.

Fabulous new signage at the start of the causeway leading to the island.

The square shapes in the salt marsh are former oyster beds.

Another stretch of sea wall, this time out in the marshes.

In the field on the mainland, flocks of geese were congregating. The noise they make when they are disturbed and take to the air is quite amazing.

One of the deeper channels in the mud, at the end of a stretch of sea wall. The depth of the channel shows the power of the tide. Northey Island and its causeway serve a strategic function in slowing the impact of the tide as it approaches Maldon. It defends homes there from flooding, just as it was a defensive point in 991 AD when the vikings invaded (leading to the Battle of Maldon in that year).

View across to the wreck of a Thames Barge. Apparently this was placed here deliberately as a permanently moored floating accommodation.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)