The church of St Michael the Archangel at Booton in Norfolk stands on the road leading to Reepham. Reepham is famous for its churches, at one time boasting of three of them within the same small Norfolk village (it was to do with three adjacent parishes wanting their church built near to a shrine, we were told when we visited). The church at Booton adds to this church-building reputation by virtue of its size, scale and audacity.

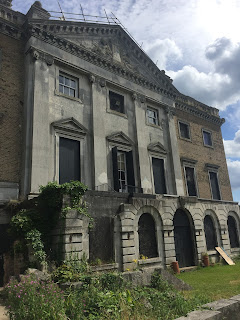

The building is duplicitous. It occupies the same floorspace as an original medieval parish church. But it is largely a fabrication of the late 19th century. The original church was almost entirely rebuilt by the rector, Whitwell Elwin, editor of the Quarterly Review and, somewhat improbably, a descendant of Pocahontas. Elwin became vicar here in 1849 and aside from forcing the GPO to install a letter box (such was the volume of his correspondence), his major achievement was rebuilding the church between 1876 and 1900.

Somewhat amazingly, Elwin designed the whole thing more or less himself, despite having no formal architectural training. A baptistry and vestry were added, as were two very striking towers at the west end, which today give the church its signature outline. Inside, a vast hammerbeamed roof soars overhead, with carved angels gazing down, whose original purpose was to support lamps. The angels were carved by the man who carved the bull’s head that still features as the logo for Colman’s mustard.

Apparently much of the inspiration came from Elwin’s travels across the country, visiting different churches and taking detailed notes. This magpie style is reflected in the various architectural features across the church: porches, doorways, recesses, windows. The whole effect is rounded off by the stained glass (by Cox, Sons & Buckley) - a unified scheme for the building, which further adds to its rarity (it all looked very pre-Raphaelite to my untrained eye, but apparently Elwin was a severe critic of the Brotherhood).

Such is the effect of this architectural extravagance that Edwin Lutyens apparently declared the church to be ‘very naughty, but in the right spirit’.

Our visit to St Michael the Archangel was affecting for a number of reasons.

First, we were there to try out a night of Champing. This new(ish) idea is the genius invention of the Churches Conservation Trust, which has looked after the building since 1987 (no small undertaking, given its idiosyncrasies). Champing involves camping. In a church. We were trying it out for the first time, and found the whole thing to be great fun.

The booking process was simplicity itself (do visit their website). The arrival instructions were emailed in good time, and were very clear to follow. When we got there, we found the beds already laid out for us, and a carpeted area installed with camp chairs and bean bags. A kettle was the only means of sustenance (Champing does not involve cooking in churches or their churchyards), and a neat outside eco-loo was the only other mod con. Aside from this it was just us, our duvets, and the church itself, for the night.

I recommend sleeping in a church. It is less spooky than it sounds. After hot chocolate, we turned all the lights off and settled down to sleep. I was conscious of the vast vault of the roof above us, and the angels looking down on us. I was conscious too of the bats flitting about at the very top of the church. But I had a very good night’s sleep indeed. We woke naturally, as the early sun seeped through the stained glass. Champing turns out to be a simple idea, brilliantly executed, and well worth trying out.

The second affecting aspect of our stay happened very early on. We had just arrived, and were unpacking our stuff. A man and his young son were wandering about in the graveyard, and then wandered into the church itself and began examining the building from the inside. At first this was quite disconcerting - didn’t he realise he was poking around in our bedroom? But I suppose this is part of the Champing experience - making private for one night what is, in reality, public space.

Anyway, we got chatting, and it turned out the man was from Holland and on his annual visit to St Michael the Archangel. He was visiting because a relative, his infant brother, is buried just outside the west end of the church building (his brother died in 1977, and special permission had to be sought for the boy to be buried in this spot). The man had no idea it was possible to sleep in the church - he was simply there to tidy up the gravestone. We were pleased to tell him about Champing, and I like the idea that one day he might come back to spend a night so close to his brother’s grave.

A third revelation (of sorts): visiting Reepham for our delicious breakfast (at the Dial House: all included in the Champing ticket) I was looking at some second-hand books and across Stephen Fry’s memoir Moab is my Washpot. I am sure I have read this already. Anyway, I was flicking through it, and discovered that St Michael the Archangel features, in a black and white photographic plate. This was because Fry spent his boyhood in Booton, either in the large house adjacent to the church, or another one close by (I couldn’t quite work out which). Fancy that.